Just a few decades prior to the first Punic War with Carthage, Rome tangled with another perilous enemy. The second cousin of Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus of Epirus inherited his relative’s genius for military strategy. The Carthaginian general Hannibal ranked Pyrrhus as second only to Alexander as the greatest general ever to have lived. Though he eventually met an ignoble end, Pyrrhus won many victories against the Romans, among other enemies, and his history lives on today in the expression that bears his name: to win a Pyrrhic victory.

Pyrrhus and Rome

Pyrrhus was born a prince, the son of King Aeacides of Epirus, a region lining the west coast of the Grecian Peninsula. When he was two years old, civil unrest forced his father to flee Epirus and the family took refuge with the Illyrians, a neighboring tribe. He fought to regain his kingship throughout the period of wars following the death of Alexander, and was finally captured and sent to Alexandria as part of a deal between Demetrius of Macedonia and Ptolemy I of Egypt. Luckily for Pyrrhus, Ptolemy was an excellent captor. He released Pyrrhus, gave him his daughter, Antigone, in marriage, and helped Pyrrhus win back his throne in Epirus.

In the early 3rd century B.C., a Greek city on the Italian Peninsula called Tarentum begged Pyrrhus’s aid against Rome. Pyrrhus thought for sure he could handle a fight with the Romans. It was an ideal opportunity to expand his territory and create his own empire in Italy. He set sail from Epirus with a massive army of about 20,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, 2,000 archers, 500 slingers, and 20 war elephants, ready for battle.

Pyrrhus’s Epirote infantry fought in the Macedonian style phalanx, a deadly fighting tactic, and the Romans were no match for his terrifying war elephants. He won several victories, driving back the Romans decisively until he met them in the Battle of Heraclea. Pyrrhus won the day, but both sides lost many men in the bloody engagement. He attempted to negotiate a treaty, no doubt much to his own advantage, but the Romans rejected it. Both he and the Romans disengaged for the winter months, Pyrrhus and his army spending the time in Campania.

The Battle of Asculum

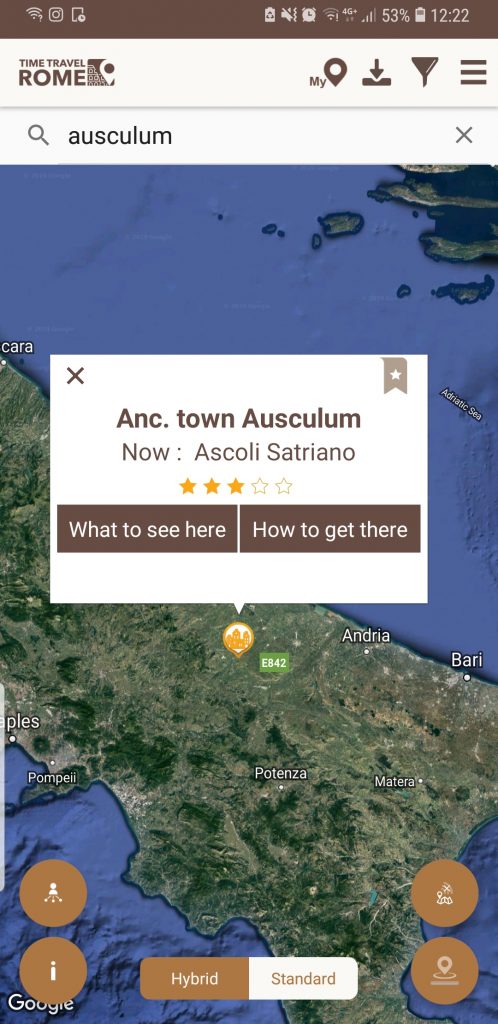

The next year, Pyrrhus moved into the region of Apulia, and camped near the city of Asculum. This would be the site of his final great battle with the Romans. Three historians tell the story of the battle, with a number of discrepancies in their accounts. However, it appears that the Romans had learned from their earlier defeats. They forced Pyrrhus into a battle near the banks of a river with many trees surrounding it. Unable to use cavalry and elephants, the two infantry lines fought viciously for the entire day, only pulling back when night fell. The next day, Pyrrhus was able to spread his line further. Leaving some of his men to occupy the wooded area, he led the rest around to where he could force the Romans into an open battle, more favorable to his cavalry.

Pyrrhus’s elephants charged the Roman lines, but once again, the Romans responded with ingenuity. They had invented special anti-elephant forces after the last battle. Archers and slingers rode on specially designed wagons which had wooden and iron poles, tridents, spikes, and scythes, all designed for use in any direction. Three hundred of these wagons met the elephants, and slowed their advance. Meanwhile, the Roman infantry “fought fiercely with their swords against the spears, reckless of their lives and thinking only of wounding and slaying, while caring naught for what they suffered.” (Plutarch). If they could only break Pyrrhus’s infantry lines before the elephants got through, they might win the battle.

Withdrawal from Italy

It was a desperate attempt, and ultimately unsuccessful. Pyrrhus’s army fought no less intensely and even more so where Pyrrhus himself led the attack. The Romans couldn’t break the infantry. Before long, the elephants broke through, and fell on the Roman soldiers with terrible strength. The Romans broke and retreated. Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote that together, the armies lost over 15,000 men. After the battle one of Pyrrhus’s commanders came up to congratulate him on the victory. Pyrrhus famously replied “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.” The battle gave rise to the phrase, “a Pyrrhic victory,” that being a victory where the losses are so great that it was almost not worth winning.

Pyrrhus and the remainder of his army retreated back across the channel to Epirus shortly after. For while Roman allies were pouring in to reinforce them, he could get no support from his own. He had also seen the tenacious spirit of the Romans, and was surely reconsidering his hopes to conquer them. Despite the withdrawal, Pyrrhus continued in his restless quest for military victory and expansion. He won many more victories during his reign, until he eventually met his own sad end. In 272 B.C., he involved himself in a civil war happening in the city of Argos.

The End of Pyrrhus

By a misunderstood order, the whole of Pyrrhus’s army, including war elephants, poured into the crowded city streets. The resulting mass of bodies was so chaotic that they had trouble moving and continuing to fight the enemy. One elephant trampled through the crowd, searching for his slain rider. Finding his fallen master, the elephant picked him up with his trunk, laid the body across his tusks, and rampaged through the city, killing all in his path. Pyrrhus found himself in deadly hand-to-hand combat with a soldier of Argos. The soldier’s mother, taking refuge on a rooftop overlooking the struggle, became worried for her son and hurled a chunk of roofing tile. It struck Pyrrhus squarely on the head and knocked him unconscious. He was decapitated, incompetently, by an enemy soldier just as he began to recover.

Sources: Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, Cassius Dio, Roman History, and Frontinus, Stratagems

Photo: Tétradrachme, Argent, Incertain, Épire, Pyrrhus by Pyrrhus (0318-0272 av. J.-C. ; roi d’Epire)is licensed under CC0

This article was written for Time Travel Rome by Marian Vermeulen.

What to See Here:

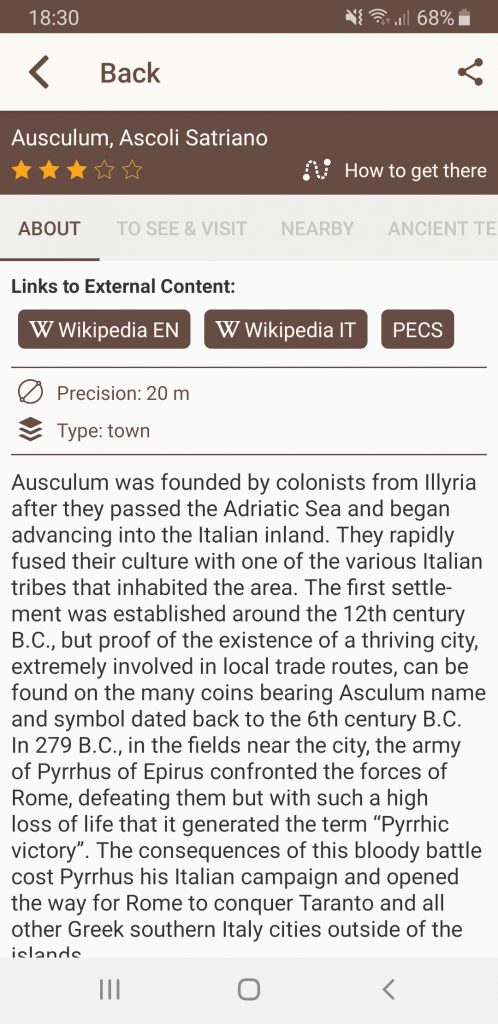

The modern city of Ascoli Satriano stands on the location of ancient Ausculum. The archaeological heritage of the city includes the Archaeological Park of the Daunians, located on the Collina del Serpente (the Hill of the Snake), a roman bridge across the Carapella river, and an underground Roman aqueduct. Some 5 km from the Ascoli, there is a luxury Faragola villa, which possibly belonged to the Scipioni Orfiti family. Unfortunately, in 2017 Faragola villa museum was destroyed by fire.

To find out more: Timetravelrome.